<39-15>

ESEA Community Centre

Media: Casted Bronze

Date: 11 /2025

Size: 12 x 15 x 10 cm

The work takes the form of an archaeological map of an ancient Chinese tomb—one that spans thousands of square meters—and folds it into an unsteady chair.

These tombs were originally constructed as underground palaces, providing the deceased with chambers where they could rest, preserve their memories by tomb mural, and safeguard valuable possessions. The funerary ritual treats the dead as if they were still living, and the tomb serves as a bridge connecting the world of the living with the heavens.

I inherit this cosmology of multiple universes and the imagination of immortality. At the same time, within such a cultural context, contemporary individuals seem to always exist in temporary roles—living in transience, constantly shifting while on the move.

This contrast between the pursuit of eternal life and the accelerated brevity of the present inspires me to imagine turning these grand archaeological terrains into miniature objects of everyday use.

<Itch>

Con-Temporary Gallery

Media: Cardboard, Steel Cable Tie, Oil Sculpture Paste, Sequin, Figur Miniture

Date: 09/2025

Size: 10 x 15 x 15 cm

Placed over a loose section of floor grating within the exhibition space, I constructs a miniature room-within-a-room, complete with a resting guest. Industrial materials are adorned with delicate fingernail charms, transforming the structure into something at once fragile yet defiant, a presence that fails to dissolve into the room around it.

<Junk Time> + <Pipeline>

MA Degree Show, Chlesea College of Arts

— Contemporary Archaeological Practices Based on Commodity Culture

Media: <Junk Time> – Mild Steel, Concrete, Silicone, Resin, Antique household items, Glass Work From Family, Daily Objects / <Pipeline> – Polypropylene, Resin

Date: 07/2025

Size: Varying Sizes

Back at home, I keep an aging plastic “urn,” stuffed with handwritten letters and small gifts from friends. I began collecting them when I graduated primary school and continued until I left my hometown. People keep keepsakes to remember one another, to soften time slipping away. When our bodies reach their end and we bid farewell, these tokens still carry weight. That’s where the name “urn” comes from.

After moving to London, I felt surrounded by a culture of urns. The more I explored antique markets, the more this sense deepened. Once, a vendor sold me a rusty silver object for £15. It was shaped like scissors, with a hollow handle for snuffing candles. Later, visiting the V&A Museum, I saw an almost identical piece on display. It struck me I had casually purchased a fragment of English life from a century ago.

I wanted to create my own museum, a kind of mobile memorial. But I had no such silver pieces. My urn at home is too private; its contents hold no exchange value, only bringing storage costs. My antiques are plastic crowns, toy fans, symbols of manufacturing stamped “made in China”—bright, cheap, precise, endlessly produced, swiftly discarded. I wanted to use these intimate materials to conduct an archaeology of junk time, to make transparent plastics and concrete do things they were never meant to do.

Then by chance, I read about the busy Lidl on Aungier Street in Dublin, where people preserved remains beneath the supermarket by sealing them under glass. Beneath lay the staircase of an 18th-century theater and flooring of an 11th-century building. Shoppers could glimpse medieval history while picking out groceries.

I began to adopt this way of preserving architecture in my work—except my subjects were commodities and consumers on the other side of the glass. Acts of consumption and use rarely freeze into moments that become history; they exist more in numb habits. By observing and making this visible, I created <Junk Time> and <Pipeline> which stand as archaeological sites of the present.

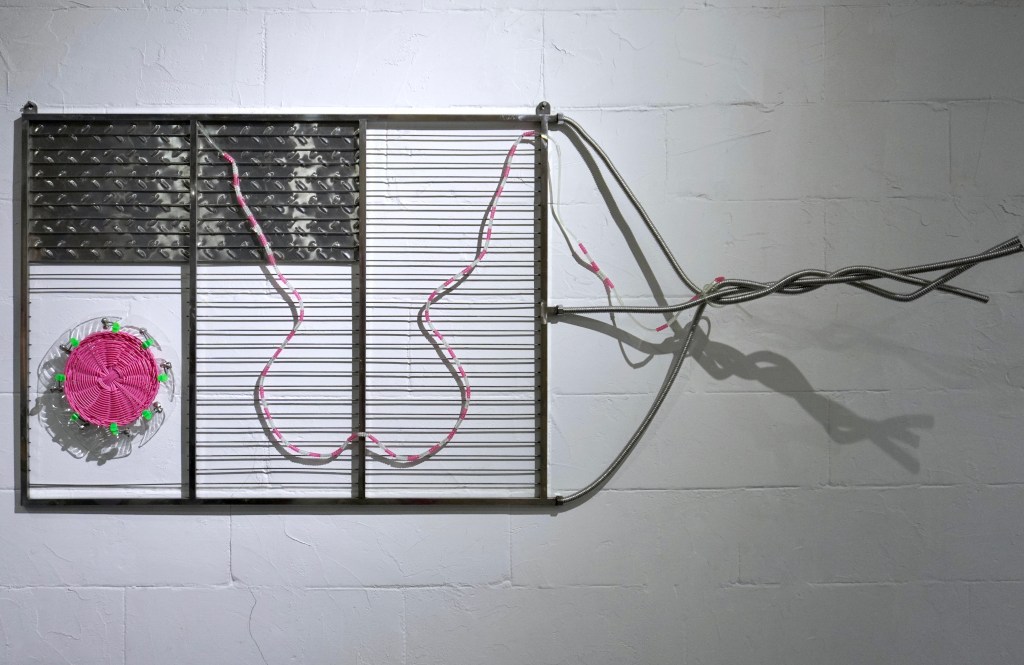

<Pipe>

The Half Space, Changsha, China

Media: metal, PVC jump rope, plastic fan blades, plastic coasters, fish bell

Date: 03/2025

Size:114 x 84 cm

Pipe draws its materials from the Gaoqiao Wholesale Market’s building supplies and general goods section. In this densely packed manufacturing hub, mass-produced objects—once symbols of collective memory and commodity culture—saturated the artist’s entire youth. Today, they continue to circulate in forms both fresh and outdated, becoming plastic antiques that neither decay nor appreciate in value.

<The Nipple of Time>

Cookhouse Gallery

Media: Silicone, Metal, Zipper, Clock Parts, Antique Shoes

Date: 02/2025

Size:80×40 cm(Suit with Hanger), 17x37cm(Plate), 60x60x50 cm(Chair)

<The Nipple of Time> is a space composed of a series of characters: a lonely white-collar worker treats the cold appliances in her home as lovers. When she leaves, the objects in her house begin to grow her skin and form, influenced by her breath, hoping to feel her love in this way.